Aunt Chick's Story

A turn of the

century baking visionary

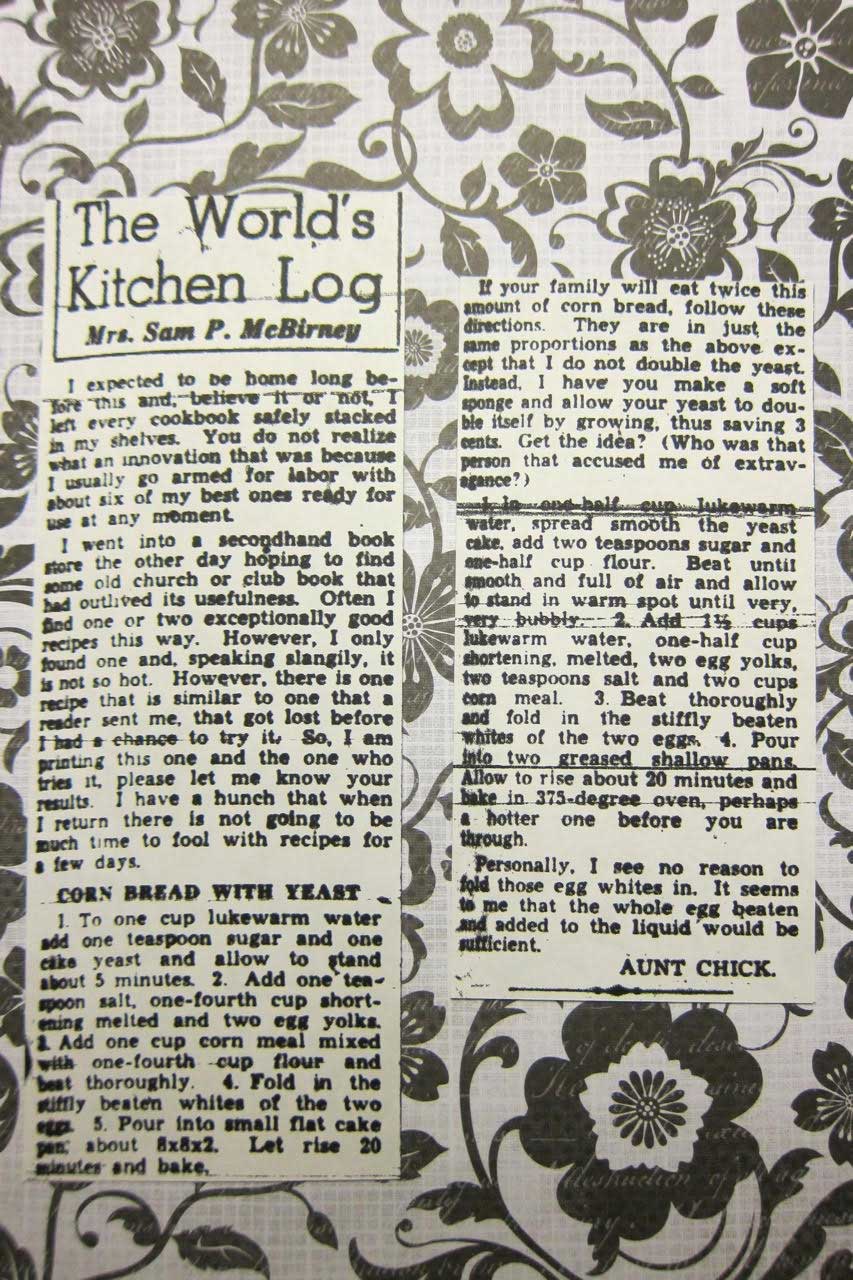

Tulsa’s best-known cook, Nettie Williams McBirney, was a nationally known culinary problem-solver who certainly did cut a “die-dough” when she was “Aunt Chick” in her Tulsa World cooking column.

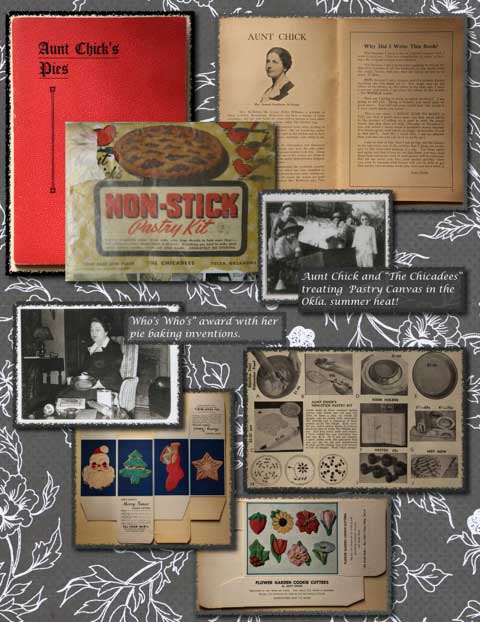

Her Christmas cookie cutters, launched in 1948, are cherished today as treasures from antique shops. The sweet fashion of her Christmas cutting molds was of a Santa, a star, a Christmas tree, a toy-filled stocking. They were sold by millions all over the world. Some cutters are still sold at Denise’s Cake Decorating and Candy Supplies and through the mail at “Aunt Chick, ” P.O. Box 1154, Broken Arrow, OK 74012.

In Here Private Life

In private life she was Mrs. Sam P. McBirney, wife of a banker who was coach of one of the best football teams this town ever produced. He had a championship team in 1916 when the University of Tulsa was called Kendall College. The celebrated team’s long-standing records captured the fancy of Eastern sports writers and their expertise prompted oil men to put up money for the Tulsa team to play Notre Dame. The game was never played. The Fighting Irish didn’t have the nerve to face them, claimed Tulsa fans.

Nettie certainly upset her private life when the Tulsa World decided she could do a cooking column under the non-de-plume of “Aunt Chick.” Without telling her husband, she began the column at a time when Oklahoma was still suffering from the Great Depression.

One morning at the breakfast table, Sam, the senior McBirney, opened the paper to her first column which was signed “Aunt Chick,” Nettie’s pet name. It was his first inkling that she had taken a job.

“That crazy woman will start a run on the bank if people think she has to work!” he shouted, bounding up the stairs three steps at a time.

Writing Her Cooking Column

She wrote the Tulsa World cooking column for 20 years, quitting in the early 1950s. When she retired to a nursing home at the age of 90, Aunt Chick gave cooking lectures to staff and patients.

By this time the whole world had learned to use her cookie cutters and her pie tins with a special wire-bottom that kept new housewives from have soggy-bottomed pies. They also used her famous stick pastry cloth with a ball-bearing rolling pin — once used by pastry cooks everywhere.

She had a head for solving difficulties that had plagued cooks through history. By listening to everyday problems, she learned how women corrected their mistakes and then set about testing their solutions before spreading the good news.

Cooks had forever put up with weepy meringue, for instance. When Aunt Chick talked about the problem during a pie class, a puzzled bride said she had no trouble with weeping meringue. She mentioned that she had a broken oven door that wouldn’t close all the way.

Aunt Chick quickly checked and sure enough, a slightly opened oven door was the answer women had been seeking for generations. Leaving the oven door ajar when baking meringue pie has been precious wisdom ever since.

Besides being a woman who understood that necessity is the mother of invention, Aunt Chick listened to women who cooked full meals for a family. She knew they usually had plenty of good advice to offer. She always tested the recipes she published and learned that a good home cook knew more than most experts.

Women asked most often about making pie and Aunt Chick enjoyed teaching them how to make luscious pies. Her cookbooks were rich with dessert recipes.

A native of North Dakota, she was educated in home economics and graduated in 1913 from the Stout Institute in Wisconsin. After she moved to Claremore to teach, she found a sleeper clause in her contract that added lunch for 125 students to her duties.

After two years of listening to girls who had to cook lunch and clean up, she became supervisor of home economics in Muskogee public schools and quickly changed her lifestyle — as we say today.

She married McBirney and moved to Tulsa when Fifth and Main streets were way out of the business section, and their home at 16th Street and Denver Avenue was in the country. Sam McBirney founded the Bank of Commerce and died a town legend in 1936.

When she first came to Tulsa she kept it secret that cooking was not a consuming passion with her, but she found a natural interest in being chairman of the cafeteria committee for the YWCA. Later she became chairman of the Junior League tearoom committee.

She was a chairman of the United Way Fund and later became a member of the New York City Junior League Tearoom Committee.

A Businesswoman

Aunt Chick became an international figure for her culinary inventions and made a splash in the field by organizing teams of cooks trained to demonstrate cooking. Such teams were employed at big department stores like Macy’s in New York City and in many major cities across the nation.

The cookie cutters made in Tulsa by the family firm called the Four B’s were her chief claim to fame. The edges were turned in a way that kept the dough from sticking.

The cutters were an instant hit, making her famous and gaining her international recognition.

Fans included Princess Margaret, who purchased a set of the Christmas cutters for Prince Charles’ fourth Christmas in 1952. That set was introduced in 1948 and was followed by other holiday sets, seasonal sets, plus a flower set for tea cookies.

Once, Wrigley’s Gum purchased cutters as a premium and then sold 70,000 of them in six weeks.

The cookie cutters’ popularity soared even though the family bought only one ad after 1947 and that was when all proceeds were donated to the Children’s Memorial Hospital in Omaha, Neb.

Nettie's Later Years

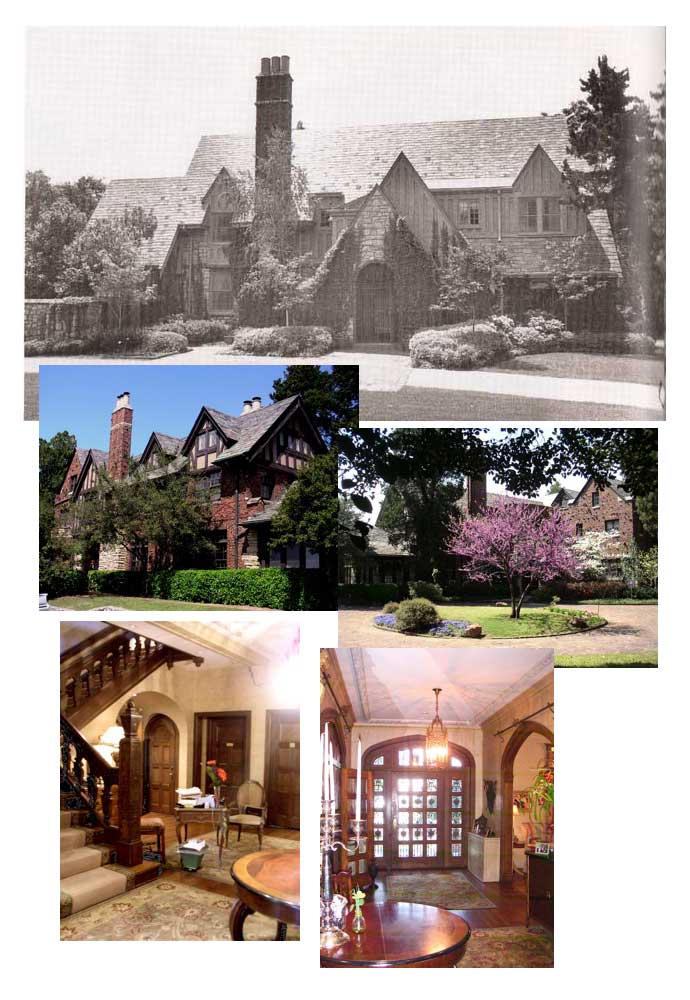

Later, Mr. and Mrs. McBirney lived in a classic English manor house at 1350 E. 27th Place. Their four children were reared in that mellow and comfortable home that was a showplace where Mrs. McBirney held cooking classes for men and women. The children who enjoyed the big house were Bill and Sam Jr., now deceased; Susan, who married W. F. Bush and lives in Tucson, Ariz.; and Mary, who married Dick Bryan and has lived in Tulsa.

When Aunt Chick moved to the nursing home she gave more than a thousand cookbooks from her collection to the Tulsa Public Library. They carry a variety of recipes with her comments on what she thought of them.

“I really didn’t take anyone’s word for recipes,” she said in a 1973 interview, “but, I do remember that one woman said I should try her lemon pie.”

The woman claimed it was the best lemon pie ever. Aunt Chick took the recipe, tried it, and agreed it was the best she had ever found.

She liked the way Oklahoma women made biscuits and fried chicken, and she found out that the secret was the kind of flour they used.

N. G. Henthorne at the Tulsa World offered her $15 a week to write her column. She took it and became the World’s best-known columnist of the day.

“I would have written about good cooking for free,” she claimed.

Reprinted with permission from the Tulsa World.

by Yvonne Litchfield

Tulsa World, Monday, July 7, 1997

Her World – Page 4

* As of July 2000, local suppliers mentioned in this article for Aunt Chick cookie cutters were no longer in business.